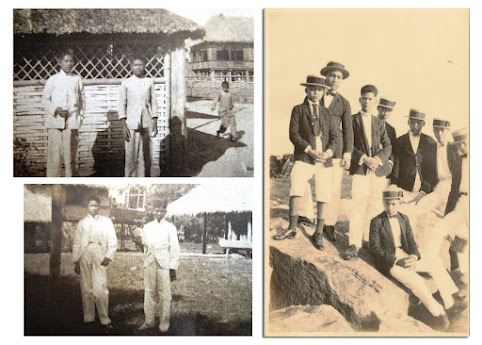

FROM CAMISA TO AMERICANA. America exerted much

influence in men’s fashioning, modernizing Filipino taste with such styles as

the classic suit, locally called ‘americana’. The ‘americana’ replaced the everyday

‘camisa’ that was favored in the provinces, as seen in these late 1920s photos.

The men on the right wore straw boat hats to complement their American look.

Filipinos took to adapting the great American lifestyle and the term “Sajonista” (Saxonist) was used to describe with a sneer, these Americanized natives, the new “modernistas”, who took to their new Western ways like the proverbial duck to water.

Names were the first to updated to give them a cosmopolitan sound—so Francisco became “Frank”, Jose “Joe” and Lucia, “Lucy”. Filipino parents had a heyday naming their babies with American appellations—Henry, Mary Rose, Helen, Charles. The young lads and lasses who went to Manila for their schooling returned home to their towns in their smart drill suits, stylish frocks, hats worn askew, copied from American fashion magazines and thigh-high stockings.

Image 3 : FILIPINOS IN CAMISA CHINOS. Two Filipino

gentlemen wearing “camisas”--collarless, long-sleeved shirts, buttoned in

front, with optional pockets. The Chinese-inspired camisa, made from

lightweight fabrics, was perfect for our tropical clime. Ca. early 1920s.

Indeed, it was from the 1920s to the early 1940s, that the peak of American impact—particularly in fashion—was most felt and seen. Even the Japanese, who displaced the Americans in the country during the War , were appalled not only at the pro-Americanism of the Filipino but at the magnitude of American influence absorbed by Filipino culture.

It is surprising to think that barely two decades earlier, young Filipino men’s everyday wear consisted of collarless camisas with buttoned front, paired with drawstring pants that can easily be rolled up, for work purposes.

For more formal occasions, the sheer barong, woven from delicate jusi or piña fiber was worn untucked, matched with a pair of pantalon de fina lana. The versatile native wear which was perfect for Philippine weather, was embellished with embroidery of the most wondrous variety. Mestizos and ilustrado dandies—favored European fashions, often incompatible with the tropical heat.

But such fashions were to change dramatically with the coming of our new masters, the Americans, who brought a whole cabinet of stylistic influences that would hasten and alter Philippine dressing tradition.

Image 5: OLD SCHOOL, NEW SCHOOL. The 1915 picture on

the left shows the standard outfit worn by Filipino boys in school—a drill suit

with standing collar, buttoned up to the neck. The Americans not only revamped

our educational system, but also the school uniform, replacing it with the

black or white ‘americana’, worn with a bowtie and paired with white pants, —as seen on the right photo

of two school lads, from 1924.

The American suit—or Americana—became ubiquitous in urban city streets and in schools, where it became a standard piece of wardrobe for men in the 1920s.

Schoolboys began shedding their plain, long-sleeved, buttoned-up drill shirts with standing collars and began donning the classic white or black Americana.

Image 6: SCHOOL IS COOL.Group of San Ildefonso,

Bulacan students pose for their high

school class picture in their pristine white ‘americana’ suit. 1924.

The suit had open, thin lapels and was worn over a close-necked collared shirt (hence the term, Americana cerrada), with a tie. The coat was matched with high-waisted, slim-fit white trousers locally called “baston” , so-called because the pants tapered off at the knees and down to the ball of the ankles, showing off the socks. Trousers also began to be worn cuffed at the bottom.

Hat tricks, shoe business.

To add to the ‘imported American’ look, our dashing Filipino ‘palikero’ went out with a straw boater hat—that had a flat top, a flat brim and a black band around the crown. Filipinos from the middle to upper class, wore panama hats, fedoras or bowler hats, while working people who spent much time outdoors wore native Western-style woven hats, replacing the sambalilos and salakots which were deemed too antiquated.

All sorts of hats and accessories could be sourced from the posh Sombreria Secher, an exclusive ‘Gent’s Furnishing Store” located at 131 Escolta that sold varias clases sombrero del pais y extranjero (various kinds of local and imported hats). Cheaper Philippine-made hats like “balibuntal” from Lucban, were also available at the pre-war Manila Hat Store along M.H. del Pilar.

Image 8: IF THE SHOE FITS. Manila was major

shoe-making center, and Toribio Teodoro’s “Ang Tibay”, which he founded in

1922, was the go-to place for locally-made, Western-style shoes. Esco Shoes,

was another pioneer pre-war shoe store founded by the American Frank Hale.

Before he stepped out, the Filipino sajonista put on his sharp-pointed leather shoes, available in different styles—two-toned, cutaway, with ‘air conditioned’ feature—which could be bought from the world-class Ang Tibay Stores at Plaza Goiti, or at their Ilaya branch. Or one could opt to go to Escolta to check out the Esco Shoe Store where proper men’s shoes could be had from 9 to 11 pesos a pair.

Suit yourself.

Image 9: MADE TO MEASURE. Avenida Rizal in Manila, teemed with master tailors, many from the provinces, who set up tailoring and haberdashery shops, to take advantage of the demand for suits of distinction, as well as uniforms of all sorts. Ads from the 1930s.

For young, style-conscious gents, only primera clase (first class) suiting materials imported from Paris by leading Manila emporiums like La Puerta del Sol, Oriental Bazaar, and Osaka Bazaar in Echague. Of course, the city’s best master cutters and tailors were entrusted by discriminating Filipinos to create their suits, in their shops clustered along Rizal Avenue and Escolta.

Image 10: TAILOR-MADE. A selection of ads from

tailoring shops touting their credentials and specialties. Of these, Luis

Liwanag reigned supreme as the master maker of suits of all kinds, vests,

tuxedos, and even church vestments! He also offered altering services.

German Adolfo Roensch Co. & Outfitters was an early haberdashery shop in Escolta that also sold men’s fashion accessories, including military uniforms. But local enterprising tailors--Kapampangans, Bulaqueños and Chinese—also proved to be sartorial masters. Tailor Luis Liwanag from Bulacan, was one such specialist in suit-making, who not only had an Avenida shop, but also ran a fashion academy (tailoring school) at the posh Crystal Arcade.

Image 11: COLLAR YOUR WORLD. Portraits of fashionable mestizos wearing different collar

types. RIGHT: A detachable stiff collar,

worn with a necktie, 1919. LEFT: Two winged collar, with folded collar

tips, worn with a bowtie and a necktie,

mid 1920s.

American shirts came also in different styles—some had winged collars that were starched, around which a tie was worn. The winged collar evolved from the Gladstone collar named in honor of British statesman William Gladstone, who popularized it. Filipino gents took to wearing winged collars to gala events as it gave them an air of class and distinction. There were also detachable stiff collars that one could purchase, fashionable since the 1850s, but which only caught on during the American rule.

Image 12: TUX

REDUX. LEFT: Man in black tuxedo with coat tails, 1913. RIGHT: A trio of gents

in identical tuxedos, dress shirts and bowties. 1920s.

For the most formal affair, however, a white tie ensemble is de riguer. The black tuxedo with coattails (swallow-tails) is also worn in glamorous events, matched with trousers trimmed with side satin ribbon strips, often worn with a vest, and black ties. Filipinos took liberties with this dressing protocol by wearing short black coats, and bow-ties.

Turncoating

on new trends.

Image 13: BALLOON-EY!. This mestizo looker is wearing

the super wide and super loose balloon pants, matched with an oversized coat,

foreshadowing the ‘zoot suit’ of the 1930s-40s. Filipinos in balloon pants were

criticized for wearing this inappropriate trouser style that made them look

even shorter.

In the July 23, 1927 issue of Graphic Magazine, an article derided the “balloon pants” as unfit for young Filipinos, who were generally short in stature. The loose, baggy “balloon”, the article contended, made Filipino men look even shorter.

By the 1930s, the Philippines was completely under the American spell. It is said that the boogie-woogie, jitterbugging kids of the Swing Era were probably the most Americanized generation of young Filipinos. An observant few were quick to lament the eradication of our values as Filipinos became enamoured with the American dream with Hollywood movies, the carnivals and cabarets, the cigarettes and the scotch—providing the cheap thrills of youthful leisure.

Image 14 : KEEPING ABREAST. The 1930s saw the

introduction of the double-breasted suit, shown here, worn with a vest, by a

trendy Filipino. The suit features

crossover panels in front, with 2 rows of buttons. His dashing mates are

wearing conventional gray American

suits. 1930s.

The period was also notable for having given us some new fashion trends. One of these is the double-breasted suit that had a distinctive features: front crossover panels, peaked lapels, broad shoulders and buttons galore—6 of them! The distinguished suit was soon being worn by Hollywood icons and royalties—including the Duke of Windsor who had his own 4-button version. Matinee idol Rogelio de la Rosa and president Manuel Roxas cut such fine, aristocratic figures whenever they went to functions wearing double-breasted suits made of expensive sharkskin.

Another ‘30s trend was the use of shoulder pads to create an impression of a larger, broader torso. The body acquired a square shape, and the peaked lapels framed the chest area. Sleeves were narrowed at the wrist. Padded suits worn with matching double-pleated, high-waisted pants would reappear in the late 40s thru the early 50s.

A style associated with the Jazz Age was the so-called Zoot suit—an extra-long and loose coat with wide lapels and exaggerated padded shoulders, paired with high-waisted, wide-legged pants that narrowed at the ankles. The look was popularized by jazz musicians—like our very own Borromeo Lou-- through the 40s decade. Vertically-challenged Filipinos stayed away from this style though, but Latinos fell for the zoot’s appeal.

Gentlemen of leisure.

Image 16: SUITS ALL OCCASIONS. The “Americana” was

worn even during moments of leisure, as in these cases: LEFT: Male revelers

sweltering in their “americanas”, stop by for refreshments at a Manila Carnival

booth in Luneta, ca. 1924. TOP RIGHT: Excursionists in Arayat. The men, by the stream,

look overdressed than the women, ca. 1917. BOTTOM RIGHT: Three pals in Baguio,

in suits, to protect them from the nippy weather.1930s.

Through two decades, the americana had an all-purpose, all-weather quality and so was worn practically everywhere—during shopping trips, while attending the carnivals in Luneta, and in out-of-town excursions to Baguio. In the 20s and 30s, excluding sports uniforms, there were very few men’s clothes made expressedly for leisure.

Men ventured into the great outdoors in loose light-colored shirts, hardy khaki pants and straw hats. Long and short-sleeved, multi-pocket loose shirts of khaki with wide collars were considered casual wear in the 1940s. Khaki gave these shirts a “military” feel, and eventually, the khaki would give way to light fabrics like cotton. By the 1950s, casual wear of this cut would have many versions—including the Hawaiian shirt, made attractive with printed resort island motifs.

Meanwhile, bathing suits were an offshoot of the sporting events introduced in the first decade of the 20th century by Americans, who were avid sports enthusiasts. The first Far East Games held in Manila in 1913 had male swimmers wearing the all-in-one woolen swimsuit in public, an abbreviated version of the first suit that had first appeared in 1870 with long sleeves and legs.

By 1925, men’s swimwear began to look similar to a wrestling singlet. This competition swimsuit found its way in men’s aparador, until it lost its top and became a pair of bathing trunks in the 1940s.

Cut and trim.

While clothes make the man, it is his well-trimmed, well-groomed hair that is his crowning glory. The first decade of the 20th century had men wearing facial hair and slicked back hair. This trend continued into the next decade, with more Filipinos doing away with moustaches and beards, and going for a slick, straight back hair finished with brilliantine pomade, for maximum gloss. The cut was neat and clean around the ear and tapered down to nothing at the nape.

This look was immortalized by Hollywood romantic star Rudolph Valentino, Ramon Navarro and “Great Gatsby” icon Fred Astaire , who were soon imitated by starstruck young men. They not only went for a full pin-straight slicked back, but added a part to one side, or in the middle. The latter was resurrected by comedian Cachupoy in the 60s who briefly gave the style his name.

Men’s hairstyles in the 1930s strayed away from convention of the previous years, as Americans sported longish hair in front and on top, with shorter side hair, and fading in the back, plastered with creams and hair tonic. Hollywood was the main purveyor of this look in the islands led by Clark Gable, Errol Flynn, Douglas Fairbanks Jr. and Gary Cooper.

The War years paved the way for short-cropped, low maintenance, military cut hair,. It was said that American soldiers sported high and tight crew cuts to control the spread of lice in their crowded quarters. Suddenly, the local Aguinaldo haircut that our first president was famous for, came into vogue again.

The Japanese attempted to promote the revival and appreciation of Filipino cultural traditions (they encouraged speaking in Pilipino) as part of its policy of ‘Asia for the Asians’, but as soon as the war ended, Filipinos once more, went “stateside” in their sartorial and grooming taste.

Boys grew their hair longer, leading to the emergence of the pompadour, where hair is swept upwards and worn high over the forehead, with sides and back upswepts. The result is high volume hair on the head, reminiscent of Madame de Pompadour’s hairstyle. James Dean and his gang of greasers of would make the pompadour famous among youngsters in midcentury Philippines.

Nearly American.

What effects did sajonismo bring to the Filipino male?

Is the white ‘saxon” culture truly fit

to be assimilated by brown-skinned Pinoys?

A 1929 article published on Free Press

paints a picture of a returning student educated and Americanized in Manila.

“Behold him as he struts along Main Street of his little town barrio, the cynosure of all eyes…a king in his own right, a sort of collegiate Caesar. The arbiter elegantiarium also, he is. …his clothes are studied, his shoes are studied, his hat and how he wears it—everything about him becomes the object of emulation and envy. Is it any wonder that, under the incense of such flattery, he feels himself a superior being, a conquering hero?”

The article ends with a call for understanding for the sajonista and his affectation of superiority complex. We paid him excessive hero worship, which he basked in—a very human thing to do. But it also left a reminder to this instant modernista—carpe diem—seize and enjoy the moment, for it will soon last. As it turned out, our love affair with America would last longer than most, and colonial mentality would continue to persist, even with the rise of nationalism in the 1950s, through the 70s and 80s.

We thought that would end when Pinatubo kicked out America from Clark with finality in 1991. The American absence cleared the air, giving us time and space to reflect on what colonial mentality has done to us, and what we have been missing all these years. But new media technology has also flung the door wide open for new influences to come in: we fell for Taiwanese F4’s metrosexual, long-hair look promoted by F4, Japanese Harajuku street fashion, and the current K-Pop rage.

Our taste for fashion defines not just our individuality but also our collective cultural identity as one nation. But whether attired in traditional barong tagalog or dressed in Banlon polyesters, Armani suit, colorful animé fashions, knitted bonnets and skull caps, drop crotch pants, mismatched prints, neck scarves and quirky Crocs—our menfolk can carry it all with confidence and aplomb, proof that when it comes to all-time porma, the Filipino is second to none.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED FOR ESQUIRE MAGAZINE, 1 APRIL 2019

SOURCES:

All Photos: Alex D. Castro Collection

Fernando, Gilda Cordero, Recio, Nik, “The Dressing Tradition”, Turn of the Century, GCF Books, Quezon City: 1978, pp. 113-133.

Joaquin, Nick. “Pop Culture: the American Years—The Filipino as Sajonista 1900s-1940s). vol. 10. Pp. 2732-2744. Published by PCPM, reprinted by Felta Press.

Sta. Maria, Felice. “The 1920s: When the Balloon Pants Came to Town”, Filipino Heritage, vol. 9. Pp. 2378-2380. Published by PCPM, reprinted by Felta Press.

McCoy, Alfred, Roces, Alfredo. Philippine Cartoons: Political Caricature of the American Era, 1900-41, Vera-Reyes (Manila), 1985

“A Suit of Clothes”, The Origin of Everyday Things, Reader’s Digest Association Ltd. © 1998. Pp. 128-129.

Wiesman, Luc. “THE MOST ICONIC MEN’S HAIRSTYLES IN HISTORY: 1920 – 1969”, 28 Mar, 2016. https://www.dmarge.com/2016/03/iconic-mens-hairstyles-history-1920-1969.html

Watkins, Ted. THE CREW CUT MEN’S HAIRCUT HISTORY, https://myhairdressers.com/blog/crew-cut-history/

THE HISTORY OF MEN'S SWIMWEAR, https://therake.com/stories/style/history-mens-swimwear/

Wikipedia.org, “Zoot suits”,https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1920s_in_Western_fashion

No comments:

Post a Comment